World Mental Health Day: We Are Only Ever “Close” To Breaking

The Times Magazine, ‘Supplement of the Year’, issue from last weekend — the 7th October 2017, if anyone’s counting.

The Times Magazine, ‘Supplement of the Year’, issue from last weekend — the 7th October 2017, if anyone’s counting.

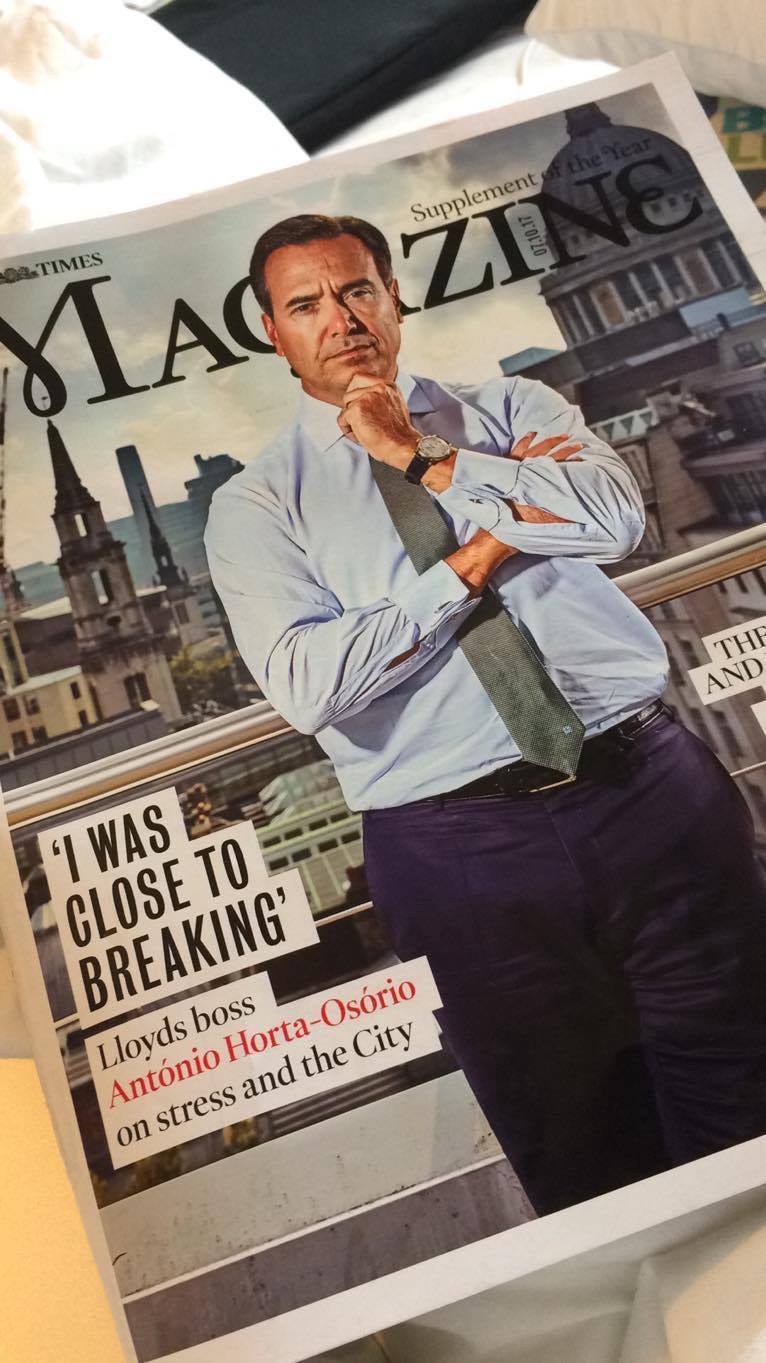

Its front cover? A little less aesthetically-oriented than normal, but no less arresting: a middle-aged man in a shirt and tie, with a hand on his chin, (expensive-looking) watch on his wrist and a gaze as thoughtful as it is penetrating — St Paul’s backdrop vying for the viewer’s attention, but ultimately sidelined. Natural assumption: this is a man of (and with) power — just reiterating status quo.

The headline? Abrasive. Confusing. ‘I WAS CLOSE TO BREAKING — Lloyds boss Antonio Horta-Osorio on stress and the City’. Abrasive because, well, this sort of thing isn’t usually talked about, is it? Not by men in power at least — and, crucially, not by men in power about men in power. ‘I’ is — procures — vulnerability; that’s why the ‘close’ is so key. Reticent, rejecting: “I was close… but I didn’t” — reframing and shaming it in one fell swoop.

Paraphrased: “Here I am, in a position of power — but I wasn’t always like this. Or I didn’t always feel like this, rather. Things weren’t always this good. But, crucially, I never fell; I never broke; I never ‘succumbed to my demons’ — whatever that means — I fought, I escaped, and now I am free.”

How noble. How hollow. How frustrating.

So close, but yet so far; as if to admit that you ‘broke’ — that you felt it and, more importantly, acted in ways that others would identify as such — is, was, the “true terror”. That Horta-Oserio, having pledged publicly to bring Lloyds back from the brink and refund the taxpayer, is described as having ‘almost broke[n] himself’ in the process, is poignant: if he had tipped into ‘a total nervous breakdown’ then he would’ve gone beyond the sympathy of a ‘crippling crisis point’ to a ‘life-or-death situation’ of his own — a state representative of the presumed fate of the bank he presided over.

‘It is relevant that his emotional honesty today… [occurs within] the safe context of his latest professional success’, Louise Carpenter acknowledges; something that is lauded as ‘the point’ — the marker of ‘a real story of recovery, rather than ongoing despair’.

But would a ‘real story of recovery’, quote unquote, not be more moving, more powerful and more inspiring if it accepted itself as such — if one were able to state proudly not that ‘it almost broke me’ but that “it broke me… and I’m back”? Brokenness is a feeling, a matter of perception; it is not — and never will be — a constant. In many ways, it is wholly arbitrary; for just as one can feel low despite having “everything to live for”, one can also feel broken despite having “everything they ever wanted”.

The reason? Brokenness is not solved externally. Neither, by implication, is it necessarily overtly visible. But does this make it any less real, any less meaningful — or, as something that is particularly relevant in this context, any less powerful?

That a man who, on the face of it, has “everything” can feel as if he has nothing is no surprise when it is (or becomes) contingent; when your life is defined by the fear of losing everything you’ve worked so hard for, its value — and meaning — is wholly representative. All that glitters is not gold; when a magpie hoards his treasure, he doesn’t necessarily appreciate it. What is far more problematic is the fact that we, too, shy away from acknowledging our own truth; overwhelmed, confused and uncertain, without openness and honesty, all of us are “broken”. But this brokenness is erroneous: it can be fixed. Not overnight — and certainly not unilaterally — but things can (and do) get better. Things can, and do, get easier. We are born, we live, we die — and in the process we learn to survive.

It’s precious: the closest thing to magic.

It’s freeing: the closest thing to wholeness.

The point? Brokenness is nothing to be afraid of. We are all a bit broken, sometimes — or, at least, we all have the potential to be.

Be brave: have some humility. Recognise that no matter who or what you are, you are still *only* human. Smile, cut yourself some slack, let yourself be.

You’re doing great.

You should be so proud of yourself. Let yourself be.

I am so proud of you.